AUSTIN, Texas — Virus mutations sound scary, especially when it’s in the context of COVID-19. So, it’s important to get the facts right.

Let’s verify a claim and show you our process.

The claim

A viewer on Facebook wrote, “Virology 101. When viruses mutate, they resoundingly weaken in virility. While it may be more infectious, the more it mutates, the more it weakens, meaning perhaps more infections but also fewer and fewer deaths. At this pace, the virus will likely mutate itself into something with a death rate less than influenza.”

Why verify this?

Several variants of concerns were found in other countries. Two of them are in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Our sources

- Dr. Ilya Finkelstein, associate professor of molecular biosciences at The University of Texas at Austin

- Dr. Peter Jay Hotez, dean for the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College Of Medicine

- Dr. William Hanage, associate professor of epidemiology at Harvard University

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

What we found

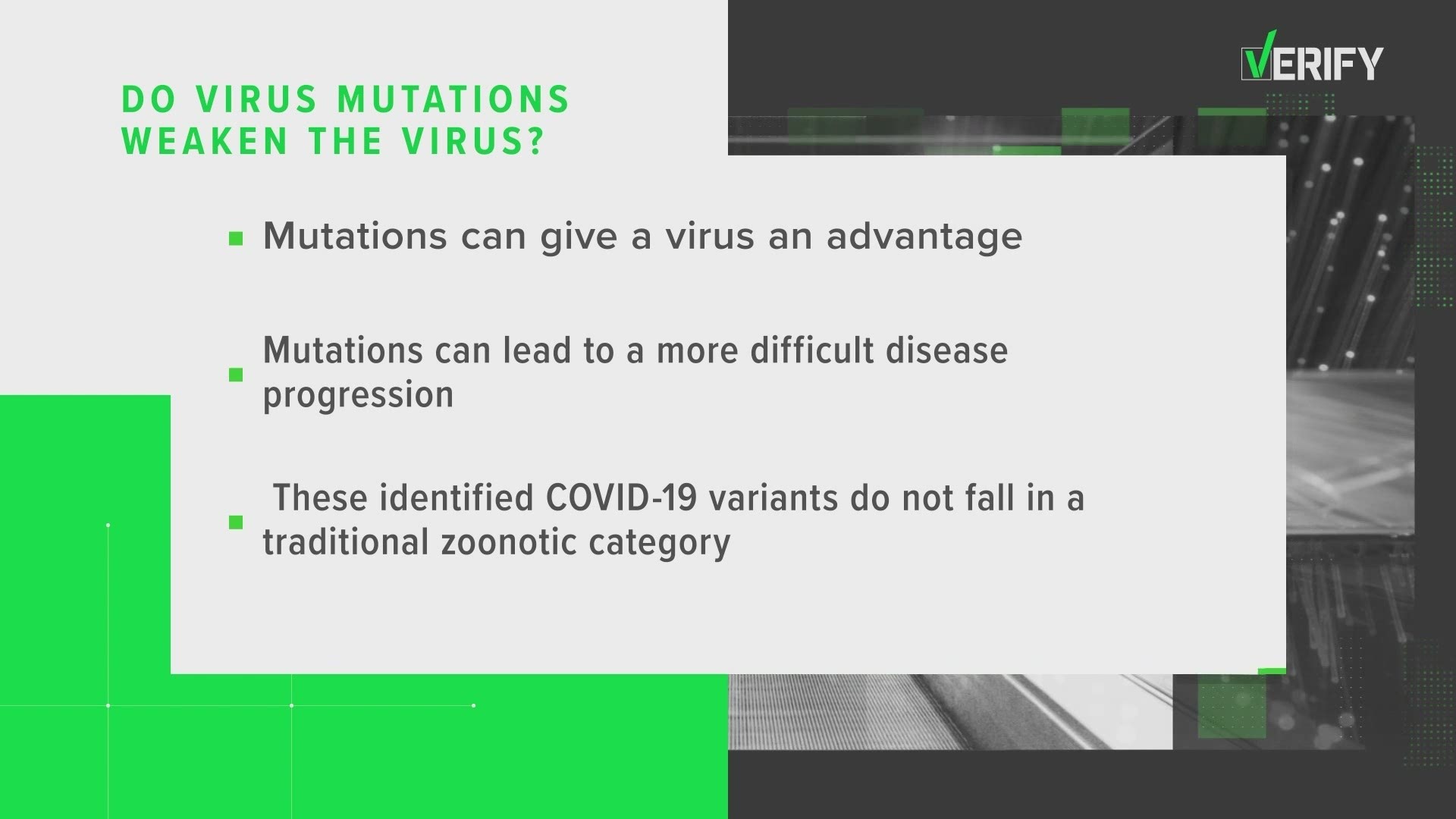

The CDC shows on its website that a variant has the “ability to cause either milder or more severe disease in people.”

The government points out on the CDC website that “there is no evidence that these recently identified SARS-CoV-2 variants cause more severe disease than earlier ones.”

Scientists we spoke with point out that mutations happen with all viruses, and they can mutate often.

“As the virus copies itself inside our bodies, it makes mistakes, and this allows the virus to evolve. When they start to rise in prevalence, that becomes something we monitor and get concerned about, because that mutation – or that series of mutations that created that variant – may have given the virus a competitive advantage over other viruses,” Finkelstein said.

“If there are enough new mutations, it becomes one that gives you cause for concern that it's changing its behavior, such as becoming more contagious or potentially more resistant to the vaccine,” Hotez said.

“The variants present a very real risk of a sting in the tail, and they will require, as I said, at the very least, the presence will require more people to be vaccinated in order to achieve protection,” Hanage said.

"Just looking at how the virus is changing, it's kind of like counting pebbles on a beach," added Finkelstein. "I mean, they're all a little different. There's many of them, and they don't really mean much on their own. But if you start seeing a lot of the same kind of pebbles and seashells, you start thinking, 'OK, there's maybe a process behind this that we need to understand.'"

Finkelstein and his team in Houston are tracking a mutation in Texas.

“Our collaborators in Houston are monitoring the clinical outcomes of all of the patients that we see once. And if these patients are coming into the higher viral load, or if I had a much more difficult disease progression, or if the clusters around them are much bigger spread, then we get concerned about that variant,” Finkelstein said.

Some viruses may weaken as they mutate.

“Some zoonotic (i.e., animal-to-human transmitted) viruses have been known to weaken as they adapt to human hosts. This may certainly be happening in many of the thousands of SARS-CoV-2 variants that have been seen already.

“The three variants of concern, by definition, do not fall into this category. Epidemiological data from the UK suggest that b.1.1.7 is ~40-50% more virulent and possibly ~10% more lethal (this is still a rough number that includes an overburdened healthcare system). The change in transmissibility and lethality of b.1.351 (first reported in South Africa) and p.1 (from Brazil) are still not known. A first glimpse of that data will come from epidemiological studies that track these variants in the general population. Please recall that we can follow b.1.1.7 a lot faster because of a quirk that allows it to be recognized via conventional PCR tests and because the UK has the best global genomic surveillance team/funding,” Finkelstein said.

One more thing the scientists pointed out as a cause for concern is that the U.S. doesn’t do a lot of finding and tracking mutations.

“It's got to be fixed, and now. This is crunch time and this is when lives are being lost,” Hotez said.

“What you really want is a large proportion of random cases to be sequenced. As it is, people like me cobble together partnerships or places and try and beg them for RNA in order to get sequences or indeed those targeted studies,” Hanage said.

Not every positive case can be tested for a mutation.

“I'll tell you how the process typically works. Typically, a patient comes in typically with a positive SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. Usually, they're hospitalized because the collection centers tend to be around hospitals or other clinical sites. Then the sputum or swab from the patient is collected. The viral particles are rapidly denatured, rapidly unfolding there. RNA is extracted and then put into a sophisticated machine that can read that RNA one letter at a time. At the end of the day, we get a report. After we do this analysis, we have a report that says, 'Here are all the letters that make up the operating system or the genetic code of this particular patient,'” Finkelstein said.

The PCR tests, such as those given at doctor’s offices and drug stores, cannot be used for tracking COVID-19 variants of concern, he added.

PEOPLE ARE ALSO READING: